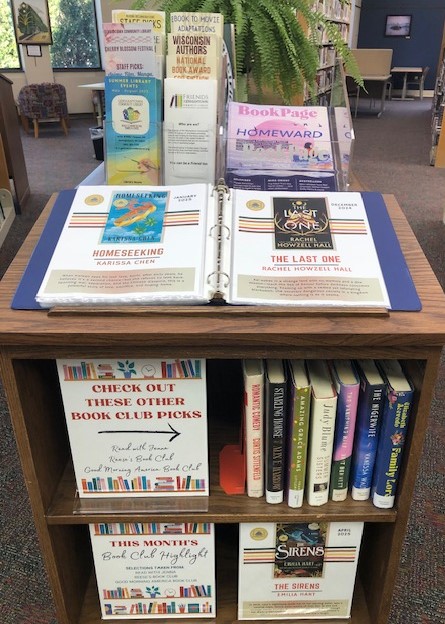

We’re thrilled to introduce a brand-new resource here at the Germantown Community Library: a monthly display featuring a book selected by a popular celebrity book club. If you’re curious about what’s trending in the popular literary world, this is the perfect way to stay in the loop. Alongside the featured monthly pick, we’ve also created a binder filled with past selections from three highly-respected book clubs: Reese’s Book Club, Read With Jenna, and the GMA Book Club.

Celebrity book clubs have grown in popularity because they offer a curated reading experience that often highlights diverse, thought-provoking fiction. Whether you’re a fan of Reese Witherspoon’s picks, Jenna Bush Hager’s selections, or the varied choices from Good Morning America, these book clubs spotlight a variety of books that resonate with readers everywhere. It’s a fun way to discover something new, especially when it comes from someone who knows how to pick a great story!

Reese’s Book Club

Reese Witherspoon’s picks often feature strong female protagonists, emotional depth, and compelling stories. Because of her love of reading, she wanted to connect with fellow readers by sharing stories centered around women to elevate their voices. On top of that, with her background in film and a knack for finding stories that can also translate well to the screen, her book club selections often spark powerful discussions. In addition to the main book club, Reese’s Book Club also has a Young Adult (YA) branch. Though selections are made less frequently, the YA picks still focus on diverse, female-centric stories that resonate with teen readers.

Read With Jenna

Jenna Bush Hager’s book club focuses on heartwarming stories, often with themes of family, relationships, and personal growth. Her selections are known for their emotional depth, thought-provoking subject matter, and their ability to connect with a wide and varied audience.

GMA Book Club

The GMA Book Club, curated by the team at Good Morning America, seeks to showcase book picks from a wide range of compelling authors, often spotlighting both new and classic bestselling works of fiction. These books are chosen for their broad appeal and strong storytelling.

So if you’re looking for some new ideas of what to read next, come check out the new display, browse the past picks, and maybe find your next great read—one that’s already been loved by celebrities and their book clubs. And don’t forget that the Germantown Community Library also offers a wide variety of book groups. Whether you’re interested in fiction, nonfiction, or mystery—or all of the above—there’s a group for you. Joining a book group is a great way to connect with fellow readers and enjoy engaging discussions. For more information, visit https://germantownlibrarywi.org/book-groups/.

Erin L., Adult Services Specialist